Imagine you’re talking to me at a party and I’ve been explaining my work to you.

I’m telling you that I’ve been working a lot recently with forms—forms like the ones you would use in your browser to log into a website, create an account somewhere, or purchase something for delivery.

Your eyes are darting around the room, looking for an escape, as I start to explain what I like about forms: What’s nice is that they communicate information explicitly and directly.

I then hand you a questionnaire and ask you to rank on a scale of 1 to 5 how interested you are in this conversation. You want to be polite, so you circle “3.” But first you had to find something to write with and then you needed to put your drink down. The question was answered, but it was cumbersome and… awkward.

There are obviously better ways to communicate and create shared understanding than having to fill out answers on a form.

In this instance, I should have been able to tell by your social cues that you were not having a good time talking to me. In any conversation, two sides are constructing their own ideas about the topic based on more than what gets conveyed through words: nuances in body language, preconceived notions, or any number of other factors. We are living, breathing, embodied human beings in a shared, tactile, sensory world. We don’t need forms to communicate.

But computers do need forms to communicate. And as a developer for Journey Group’s application studio, I work with computers. You shouldn’t have asked about my job if you didn’t want to hear about it. But if you’re bored, we can talk about something else.

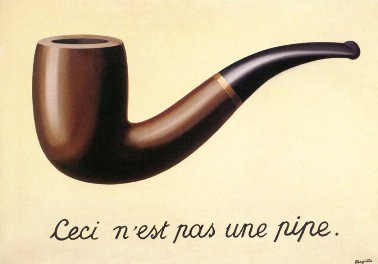

This is not a pipe

“The Treachery of Images” is a painting by 20th-century French surrealist René Magritte. It is simply an illustration of a tobacco pipe with French text beneath reading “this is not a pipe.”

That’s both wrong and right. If you look at the image, you see what anyone who’s seen a smoking pipe would describe as a pipe. Yet, it’s not really a pipe but a painting of one. You could question why the text should get more authority than the image over what it is or isn’t. Or how we know for sure that the text is even referring to the image. It sure seems like it is, but are you willing to defend that in court?

It’s a fun thought experiment, right? How can we definitively say what anything is supposed to represent? Now, we’re both pretty sure that what we’re looking at is a pipe with a lie written underneath it. But we’re the type of people who go to parties and talk about art, so we recognize that there’s some interesting nuance here.

Computers are very explicit, and they don’t appreciate the nuances of surrealist paintings.

If we, as programmers, want to represent a pipe in our code, we effectively point to some bit of data and label it “pipe.” Then if we needed to reference that data, we would find it by using that “pipe” label. Now, our pipe is a pipe, and if we ever said that it wasn’t, our computer wouldn’t work.

The actual data for our “pipe” could be a whole list of other labels for other bits of associated data. The “color” of the pipe is “brown.” The “smell” is “smoky.” The “weight” is “3 ounces.” So, if we later wanted to know what our pipe smells like, we could find out using the “pipe” label and its associated “smell” label.

This is a simple example of how computers represent data, and in actual software, there would be a vast number of concepts represented as individual pieces of data, quickly getting to a point where the labeled data itself would need to be grouped together and abstracted into its own unifying concept. We could take a whole collection of different data points all related to the parts of a website’s login form, for instance, and label it “login form.”

Having a clear label for everything that makes up that form makes it easier to talk about, even though I know you don’t think that’s very interesting. Well, let me explain why you’re wrong about that.

The picture in everyone’s head

A perennial aphorism in our studio is: All models are wrong, but some models are helpful.

A representation of something isn’t the real thing and will necessarily leave out or ignore certain aspects. But good models can be very helpful in creating a shared understanding of a subject.

When we work with our clients to design a new application, before any code is written, we’ll first create mockups of the various screens and elements so that we can agree on what the app should be like. This visual representation is the starting point for conversation and iteration on the design. It is straightforward to make changes to this model of the app, because nothing has to actually work.

The back-and-forth discussion around a mockup is partly to come up with an aesthetic: the color palette, font sizes, overall vibe. But more importantly, it’s about coming to a shared understanding of the functionality of the app.

When you make a model of the solar system, there is a real-life solar system that you can reference. If you want to represent a pipe in a painting, it might be helpful to look at an actual pipe while you work. But when a team of people needs to make a model of an app that doesn’t exist yet, everyone needs to get on the same page about what the app will actually do.

Eventually, the stars will align: The features are decided upon and the design is finalized. Then that ephemeral, shared understanding needs to be quickly written down as software code, before too much time has passed and the picture in everyone’s head turns back into a pumpkin.

Writing to share ideas

A related motto at Journey Group: Writing is thinking.

We’re having a fun, casual chat at this party, but just imagine I needed to actually write these ideas down into a coherent essay for someone else to read. It would take me months to finish!

Whenever I go to write down my thoughts on a subject, I become acutely aware of the concepts I’ve never thought through. I find holes in my logic that I didn’t know existed.

What’s more, I realize that even the things I’ve spent time thinking through might not translate well to someone else. I’m still on the fence about that pumpkin thing I said earlier. Through the process of writing, I can clarify and articulate my thoughts in a way that I can’t by just mulling things over in my head.

Writing to share ideas with another person is an exercise in empathy and imagination. This is different from writing instructions for computer programs, which require you to meet their exacting and precise syntax. And whereas the purpose of written prose is self-evident, the purpose of written software is in the application of that software. Thus the name! But both types of writing are reflections of thought being made manifest.

In our studio, once we have decided on a design for an application, we need to write the code to make it function. But, because we know that computers do not appreciate nuance, we try very hard to think through (i.e., write down) all of the details for how the software will work before we start writing the code.

From the mock-ups, we will write specification documents, create sketches and diagrams of the flow of data, and break the details down into actionable tasks. All of this not only makes us look very busy, but it also gives us confidence that we have thought well. And thinking through these details first is important because it’s easy to call something a pipe when it’s not.

The shape of something

Now, I know you don’t want to hear this, but this all relates back to the forms that I work with.

What’s nice about forms is that they communicate information explicitly and directly. But what’s tricky is actually figuring out what that information should be.

The ultimate purpose of a form is to convey information in a structure that makes sense and is meaningful to the person receiving that information. It relates to another meaning of the word “form”: the shape of something. The hard work of writing is the shaping of ideas into a form that can be communicated. In the same way, when Journey Group creates an application for a client, the actual work we do is more than just the writing of code. It’s in the forming of a shared understanding that can then be reflected in the software.

You and I both know each other well enough by now to understand that I’m not being literal when I say that it’s easy to call something a pipe when it’s not. It’s a metaphor for forms (sorry, that’s a joke). It’s a metaphor for when the picture in one person’s head conflicts with another’s.

For example: It’s easy to say that a site should allow visitors to comment on pages. You might expect that to mean a comment box at the bottom of every page. But someone else might expect that to mean that the site has user accounts and an administrator who can configure which pages have comments and which comments get shown to the public. One of those scenarios would take a lot more work to make happen, and mismatched expectations for that commenting feature would lead to some heartache at the end of the project.

What’s nice about people is that they can change their own mental model of something. If those two people talked about their expectations for a commenting feature, they could agree on a shared understanding very quickly. But it takes explicit direction and instruction in code for a computer to have its understanding changed. That’s why it’s so important to have a vision of an application that everyone agrees on before it is built.

What’s even nicer about people is that they can get to know each other. Creating a shared vision isn’t just good for application development but for any type of design project. And the longer and more fully you know someone, the easier it becomes to get on the same page about mission, goals, and login forms.

There are not-pipes everywhere, and Journey Group folks are keenly aware that this will always be the case. Our principal work will always be about helping other institutions tell their stories. And our application studio particularly values a shared understanding of that story, because a computer will never have that understanding unless we form it. And I’m good with computers; I don’t know if I need to make that clear.