My adult children love to reminisce about the ways Dad ruined their lives.

For one, it was passing along my proclivity to sweat excessively. For another, it has been my tendency toward twitchy anxiety that she ruefully inherited. And all of them love to tell the story of the time when Dad ruined Christmas. (Our beloved dog BIT one of my children on Christmas Eve and I lost my temper and kicked her out of the house. The dog, not the child.)

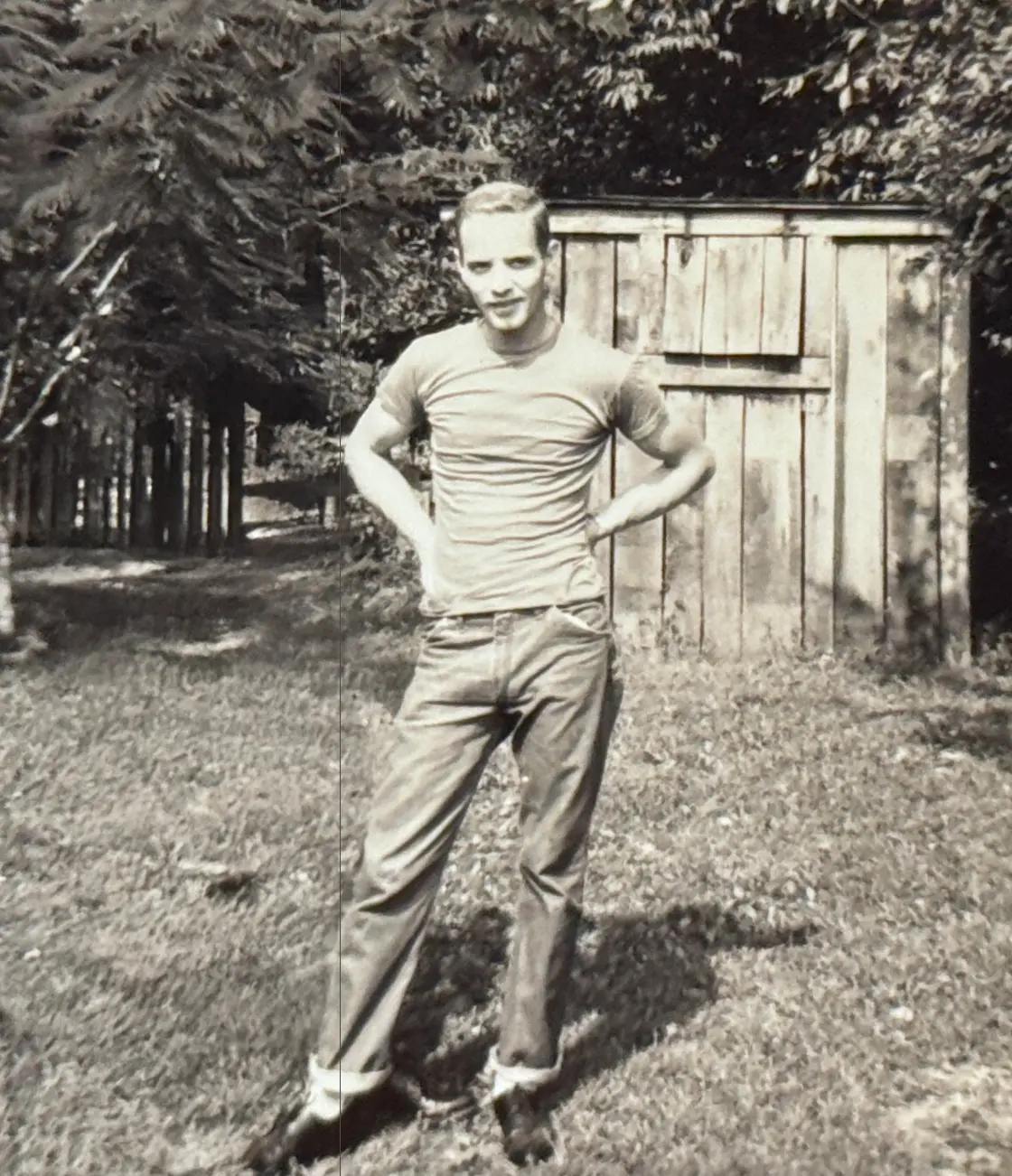

I’d like to think there were some positive gifts along the way, and perhaps time will tell. As for me, the greatest gift from my father was the love of making art. As I wrote about him in an essay some time ago: “So far as I knew, every butcher and baker and candlestick maker would come home after a long day and spend glorious evenings drawing and painting.”

This past year, though, after a series of long illnesses, my father passed away at the age of 86. Although our family knew his death was imminent, I was still surprised by grief.

But I was also surprised because, upon his passing, I think he gave me another gift. I had long admired his easygoing confidence, and no more so than when making art. Although he was very accomplished, he could never quite master perspective, as evidenced by his many barns and rivers that twisted impossibly across his canvases. But he didn’t care; he had the courage to paint anyway.

I am not proud of this, but I have always tended to be cautious and guarded when making art. I admire how my father felt the freedom to fail, whereas I have often failed to be free. But maybe that is changing.

The gesture

Only a few months after my father’s death, I had the opportunity (once again) to take a summer workshop where the making of images is regarded as the most profound method of aesthetic research. Knowing of my father’s influence on me, my instructor encouraged me to push deeper into “the gesture” and its relevance to design.

In the field of aesthetics, the idea of the gesture rests on a distinction between a practical action and one that is expressive. A charcoal line might produce a shape, for instance, but it may also reveal the urgency (or hesitancy) or perhaps the confidence (or insecurity) of the hand that made it. Gesture speaks to the latter—the way a mark discloses its own making toward evoking some sense of meaning.

In practice, this means I was able to put aside my laptop—on which I am worryingly dependent—and spend a week smearing charcoal and ink over paper and hands and face. For me, that takes a little courage.

The workshop

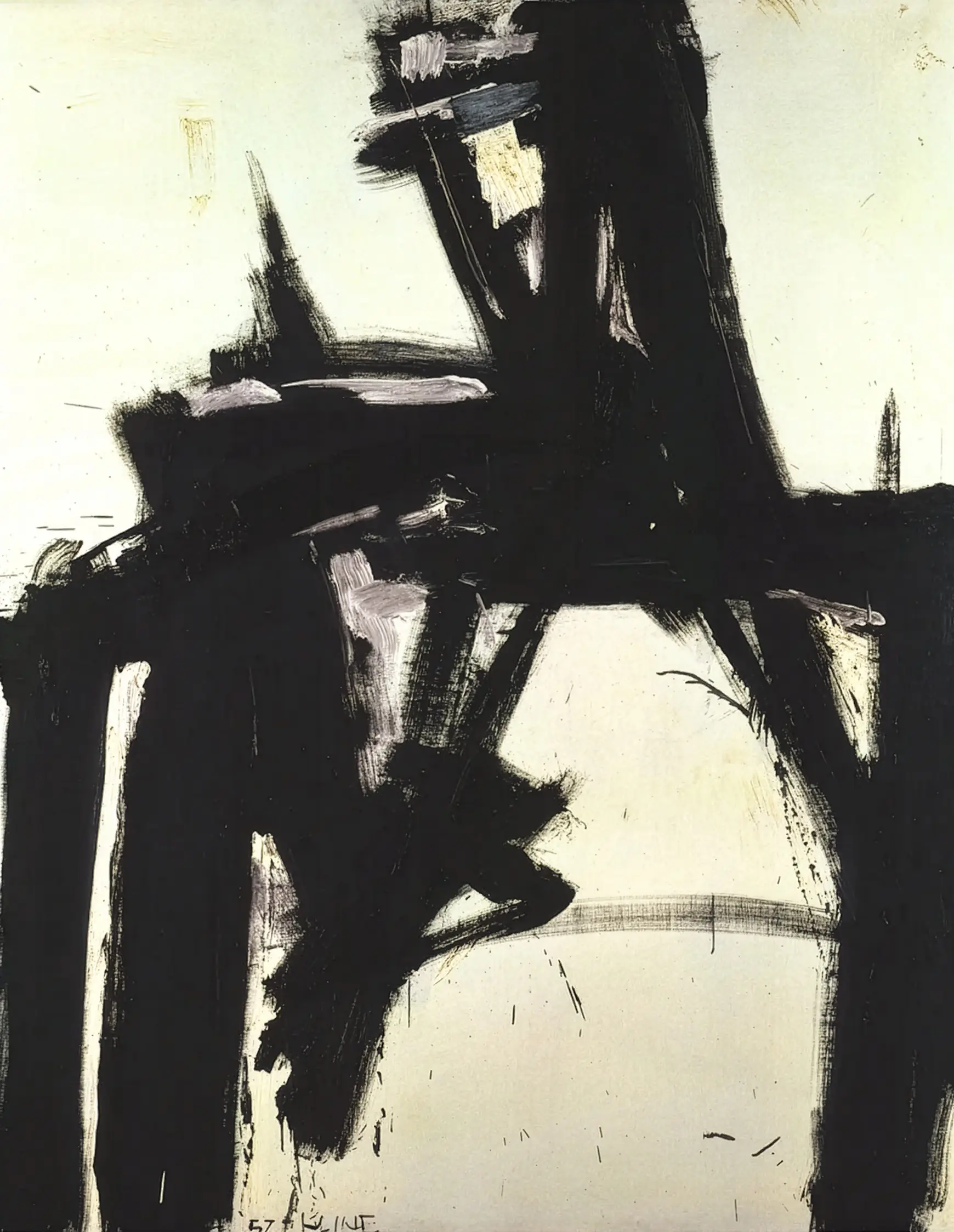

We most easily think of gestures in fine art, especially painting and sculpture, because they are so unhesitatingly perceptible. Many of the demonstrative brushstrokes of the Abstract Expressionists are reduced, or rather enlarged, by their gestures. But Baroque painters also make striking use of the gesture through dynamic, swirling compositions that create a sense of elaborate movement.

For the purposes of this workshop, however, I was curious to explore the gesture within the stuff of design. I still believe that design can be transformative and so I wondered how exploring the gesture might prove useful.

With this simple conceptual framework, the bulk of the workshop provided me time and space (along with mentorship) to create exploratory images. Because of my interest in design, I chose to focus my gestural experiments on color, type, and pattern. I made a glorious mess.

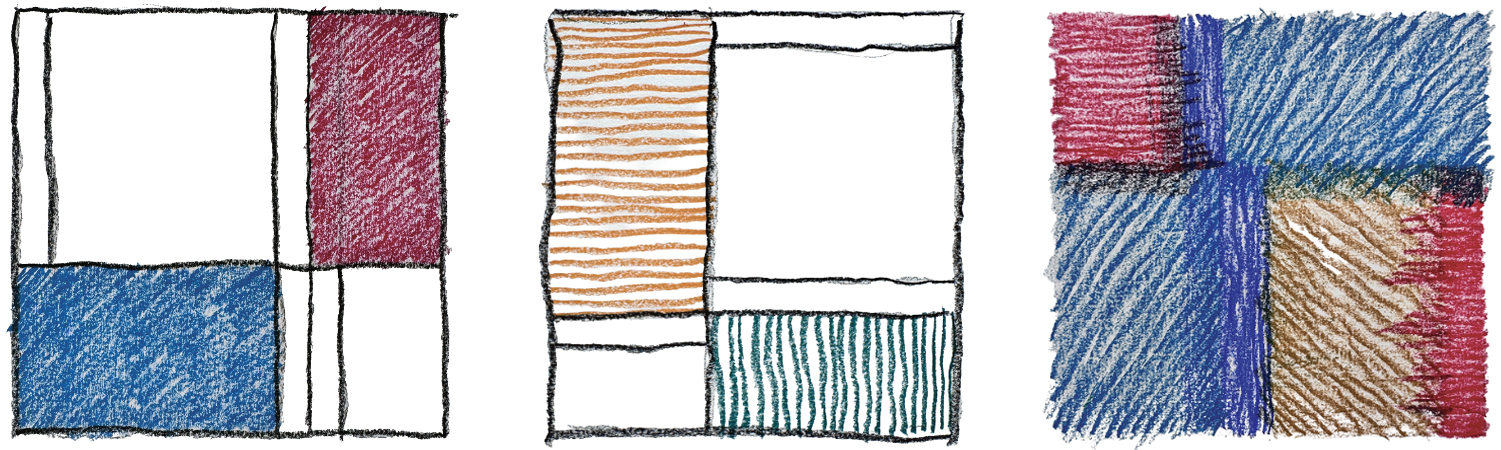

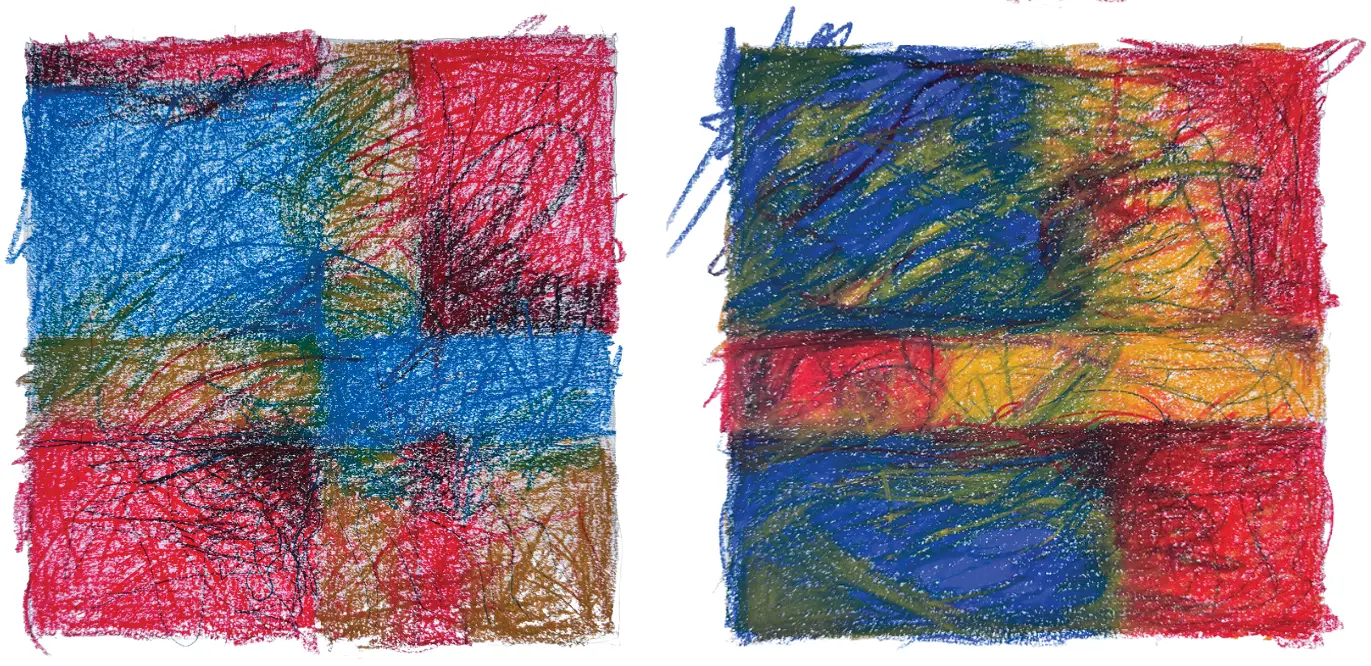

The gesture and color

Because of my tentative nature, I began the week by setting up the color experiments by drawing an almost endless array of geometric charcoal compositions. Although I felt I needed some constraints within which to play, I had to laugh when I realized I had literally created boxes to inhibit my work.

Endeavoring to “color outside the lines,” I used water-soluble pastels that, unlike chalk sticks, could yield deep, opaque color. By working quickly and creating multiple images, I soon began to ignore the charcoal boxes and enjoy how the colorful gestures began to melt into each other.

Although most of the resulting images felt timid and derivative, I found that by grinding the pastels into the paper with no small amount of energy, I began to feel a sense of relief and freedom. My final piece, which I believe was most successful, was essentially an exercise in anger management.

“If I create from the heart, nearly everything works: if from the head, almost nothing.”

The gesture and type

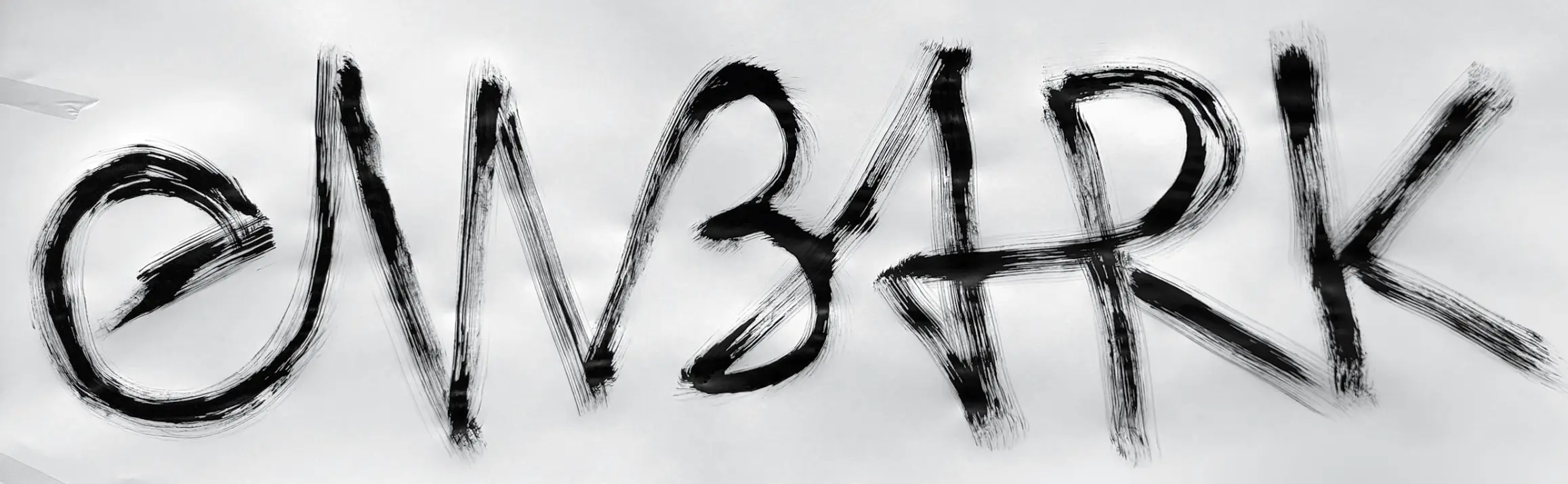

The word EMBARK serves Journey Group as a visual shorthand for adventure, speaking to both uncertainty and the promise of discovery we hope to achieve. I focused all of my gestural work on this single word to minimize the variables and endless distractions.

Realizing afresh how working quickly can generate gratifying surprises, I chose to work with india ink to explore typography. With black ink dripping from stiff brushes, my efforts felt more like writing than drawing letterforms. But that helped me avoid settling into mere craft and demanded I make gestures with urgency.

Pushing myself further to avoid stifling the work, I tried to create gestures of the word EMBARK with single strokes. By iterating quickly, I became lost in the making of the art and without making judgments about the quality of the work. There would be ample time for that.

“Drawing is like making an expressive gesture with the advantage of permanence.”

The gesture and pattern

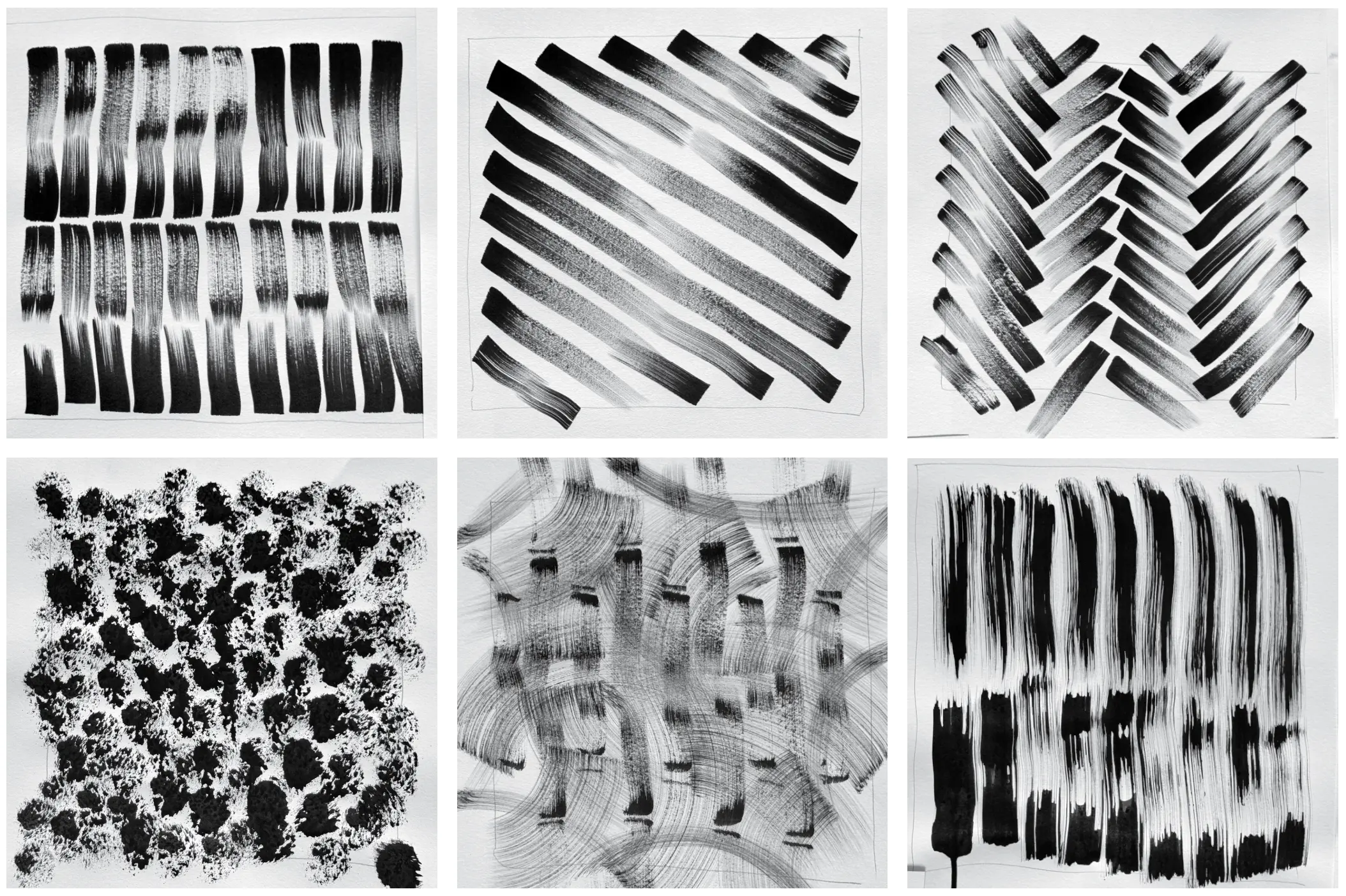

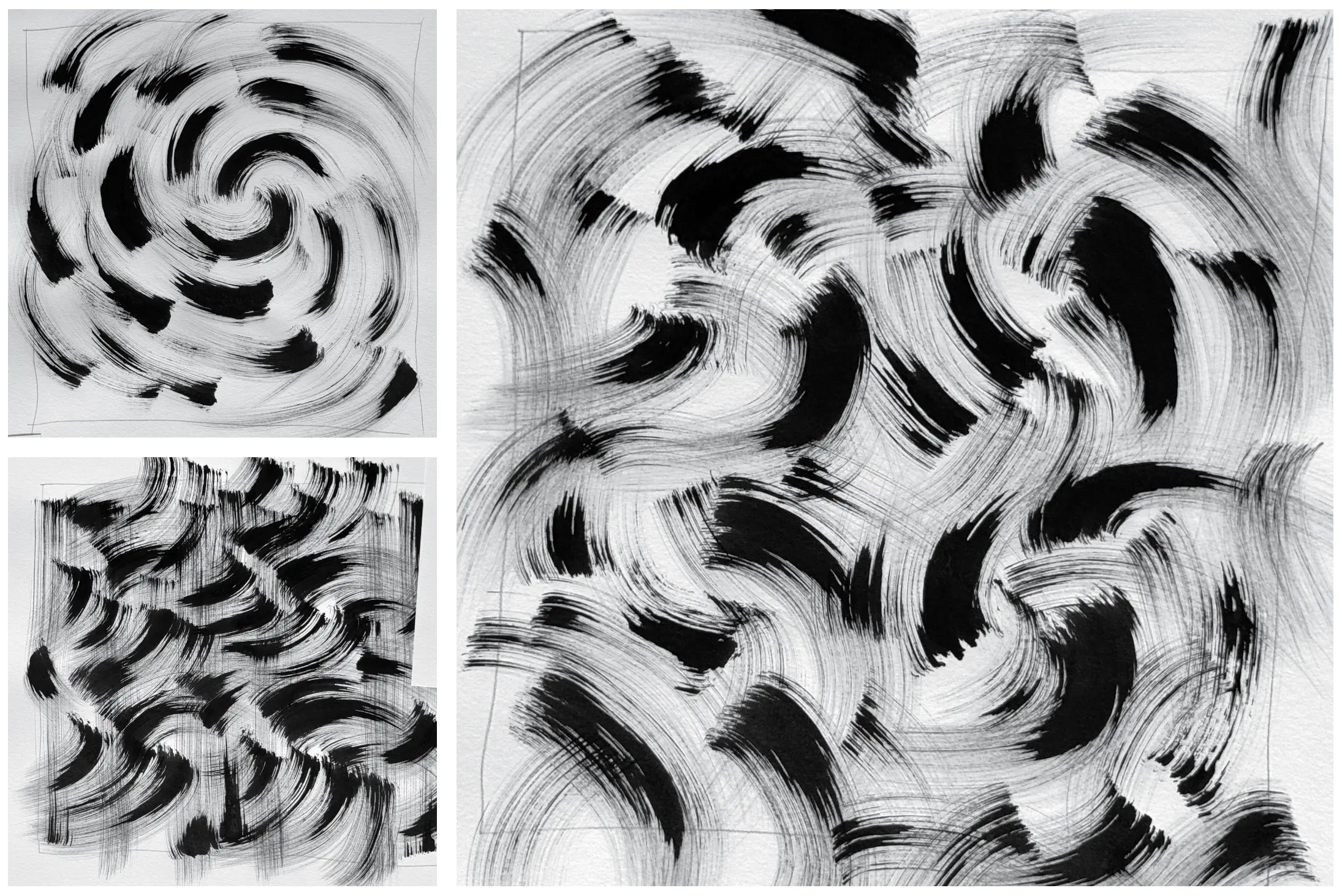

I was able to spend the better part of two days each on color and typography, respectively, so that by Friday (our last day), I was running out of time. I playfully accused my instructor of planning my time this way so that my inhibitions would be replaced by panic. And so they were.

Knowing that we were presenting our work at day’s end, I had no choice but to paint gestures of patterns fast and furiously. Continuing my work with india ink and stiff brushes, I gave up trying to control the narrative and let the patterns emerge from my brushstrokes. I somehow managed to create several dozen images within the space of a few hours. For once I was more satisfied with quantity over quality.

“It’s all craft until God walks into the room.”

More than decorative

Having offered a few faltering thoughts on each of these explorations, I am reminded of the famous quote by the modern dancer Isadora Duncan. When asked by an inquisitive interviewer about what her dance meant, she replied, “If I could tell you what it meant, there would be no point dancing it!”

In some ways, my experiences taught me what most of us already know: Losing yourself in the creative act tamps down inhibitions and stimulates new ideas. And yet I found that my most productive sessions were not accomplished by letting my mind wander but when I was focusing and concentrating most deeply.

What these explorations taught me was somewhat precognitive—learned more by the making of images rather than by reasoning alone. But a couple of thinkers, one a philosopher and the other a psychologist, suggest that more is going on here.

In his book The Meaning of the Body, Mark Johnson argues that meaning proceeds from bodily, gestural experiences before abstract reasoning. As a sensorimotor experience, gesture is part of how we understand and make sense of the world. He writes, “Gesture is not a decoration added to thought—it is a form of thinking itself.”

Adjacently, Barbara Tversky, in her book Mind in Motion, emphasizes that gestures are not just by-products of communication but are fundamental to how we process and convey information: “Our actions in real space get turned into mental actions on thought, often spouting spontaneously from our bodies as gestures.”

If it is true, as Johnson and Tversky claim, that the gesture is a form of thinking and helps us make sense of the world, the gesture plays more than a decorative role in design. Because the gesture is deeply embedded in how we think, understand, and interact with the world, it becomes an invaluable tool for visual communication. Or, in other words, embodied design.

Ultimately, the gesture reminds us that design is not only about communication but also about being in the world—about how humans act, move, and express meaning through visual form. Recognizing gesture in design broadens our understanding of how design can be transformative, restoring to design a sense of immediacy, humanity, and presence.

A little courage

Since my dad passed away, I’ve learned that many cultures, spiritual traditions and even modern psychology speak to a very similar idea: When someone you love dies, they may leave you some sort of gift—an ability, strength, or trait they embodied. I am as skeptical as the next person, but I choose to believe that my dad left me with a little bit of his courage. Perhaps I only aspire to have his easygoing confidence, but even that is a gift.

What I do believe is that more is going on than we can see, and so it is with the gesture. As discussed, the gesture can sometimes be visibly traced to something like a brushstroke, but sometimes a gesture reveals something more about the artist. This expressive act most certainly communicates—like a sense of immediacy or energy or life itself. Ultimately, however, to discern the gesture in design is to recognize design as human. And that is a gift.